Being in communion is the heart of Catholicism. We become one body in Christ at Baptism and we continue sharing that common life forever, beyond death. We are aware of this connectedness with one another every time we say in the creed: "I believe in the communion of saints."

We speak of this community each time we pray at Mass when we pray for the living and recall "those who have gone before us marked with the sign of faith."

When we baptize a baby we welcome him or her to the communion of saints. And when we attend a funeral we know that the one whose life we are celebrating is now moving from the blessed on earth to the blessed in heaven.

From the day of its initiation, the church emphasized community. After Pentecost, the apostles went out to share the Good News with others. They gathered together in homes to celebrate the Eucharist, which made them one.

Communal living was the norm in the Jerusalem church. They saw themselves as establishing the reign of God in the world. They cared for each other, worked for each other, died for each other. They were one community.

It was understood that all Christians were bonded together and had obligations to each other. As people died, they had not left the community, but had entered another state, just as Jesus had at the resurrection.

Origins in the New Testament:

In the Letter to the Romans, Paul tells us: "Just as each of us is one body with many members and all the members have the same function so too we, though many, are one body in Christ and individually members one of another. We have gifts that differ according to favor bestowed on each of us."

Paul leaves no doubt that those gifts are to be used in the service of the group. Members of this common body had obligations to build up the community and were called "saints." This comes directly out of the Jewish idea of being a holy nation, a covenanted people. The "saints" were those who had inherited the covenant.

Paul's letters are addressed to various local communities under the title of "saints" (Rom 1:7;1Cor 1:2; 2 Cor 1:1; Eph 1:1; Phil 1:1; Col 1:2). It was also applied to those whom Christians served. Paul made a collection in Corinth for the relief of the saints in Jerusalem (1Cor 16:1).

In time the word "saint" was used to designate those "who had fallen asleep," and were now enjoying their reward. "Saints" were not only of this world, but also of the world to come. A bond existed between them and the living community. St. Paul tells the Thessalonians: "We do not want you to be unaware, brothers, about those who have fallen asleep, so that you may not grieve like the rest, who have no hope. For if we believe that Jesus died and rose, so too will God, through Jesus, bring with him those who have fallen asleep. Indeed, we tell you this, on the word of the Lord, that we who are alive, who are left until the coming of the Lord, will surely not precede those who have fallen asleep" (2 Thessalonians 4:13-15).

Martyrs:

In the beginning of the church's history many witnessed to their faith by giving their lives. Most of the followers of Christ were martyred rather horrendously.

Some early saints were stoned, as was Stephen. In the Acts of the Apostles we read: "They threw him out of the city and began to stone him" As they were stoning Stephen, he called out, 'Lord Jesus, receive my spirit.' Then he fell to his knees and cried out in a loud voice, 'Lord, do not hold this sin against them'; and when he said this, he fell asleep" (Acts 7:58-60).

Tradition tells us that James was thrown over a cliff and then clubbed to death. Others were hacked to death with hatchets and many fought with wild animals in an arena for the amusement of the crowds.

Tradition has it that Peter chose to be crucified upside down. This was probably a quicker way of dying than right way up, which often took 36 hours, but was not the way most of us would choose to go.

Paul was beheaded -- not bad when you say it quickly. But when you picture this old man being taken out through the streets of Rome along the Appian Way, then tied to a tree where the executioner hacked away, it tends to make one shiver a little.

Igantius of Antioch, an elderly man, was "ground like wheat" by the teeth of animals. Perpetua and Felicity, two young women, had to wait until after Felicity's baby was born before they could face the lions. During this time Perpetua wrote down her thoughts, giving us a firsthand account of martyrdom.

Butler's Lives of the Saints runs red with stories of early martyrs and the details of their deaths. Tertullian rightly said that the blood of the martyrs was the seed of the church.

Veneration of Saints:

The various church communities cherished these martyrs and from early times commemorated the anniversaries of their deaths (their birth into eternal life) by keeping all-night vigil at their graves and celebrating a Eucharist in the early morning.

By the time Christianity became an accepted religion in the Roman Empire, the cult of martyrs was well established and they were being invoked as intercessors. Particular saints could plead before God on behalf of certain communities or individuals.

Members of the community still living on earth could intercede on behalf of those in purgatory. Praying for the dead is based on the scriptural passage in 2 Maccabees 12:43-46: "It is a holy and wholesome thing to pray for the dead that they may be loosed from their sins."

All the saints -- those on earth, those in heaven and those in purgatory -- were seen as belonging to the one body of Christ.

There was much emphasis placed on this idea of a saintly community in the early church. Saint Gregory of Nyssa wrote that Christians are united by one same Holy Spirit through Baptism and must "cleave together," forming one body and one spirit.

Tertullian wrote of offering the Eucharist for the dead that they might be relieved of their suffering.

Ambrose spoke of the church as "embracing the union of the saints and angels in heaven."

Augustine, speaking at the celebration of the feast of Perpetua and Felicity, declared: "Let it not seem a small thing to us that we are members of the same body as these. We marvel with them and they have compassion on us. We rejoice with them, they pray for us. We all serve one Lord, follow one master, and attend one king. We are joined to one head, journey to one Jerusalem, follow after one love, and embrace one unity."

John Chrysostom called for a "feast of martyrs of the whole world." At his behest the feast of All Saints (All Hallows), those known and unknown, has been observed since the fourth century.

Pope Gregory the First spoke of the necessity of praying for the dead: "The prayers of the faithful on earth and of the saints in heaven can aid in obtaining the release of those in purgatory."

The Nicene Creed leaves us in no doubt of the importance of this early church teaching. As Christians we profess a belief in the communion of saints.

How Does It Work?:

This interconnectedness is a dogma that has been observed and loved by the church through the centuries. It brings us all together as one family. It includes not only canonized saints but also all those who have died. It keeps us connected to our beloved dead. We pray for them, for whatever obligations they left unfinished, and we ask them to pray for us.

We pray for each other. We pray for our friends scattered far and wide and feel a bonding with them. We pray for those in missionary work, for those who are sick, for those being persecuted for the faith, for our pope, bishops, priests and sisters. We pray for our enemies and are thus enabled to forgive and to change our attitude.

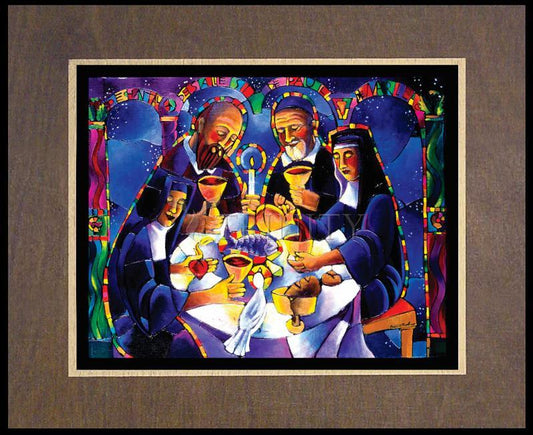

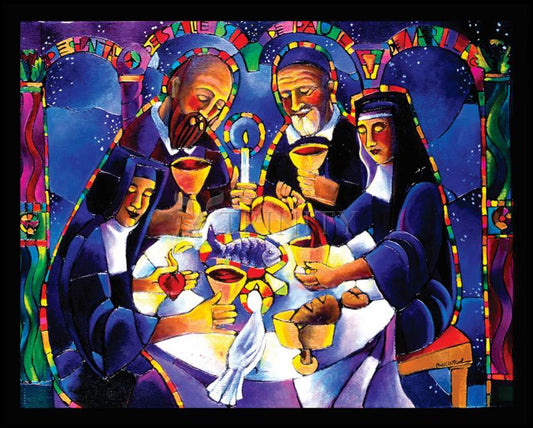

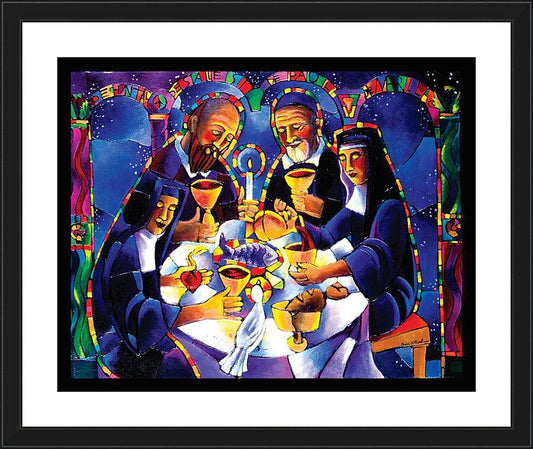

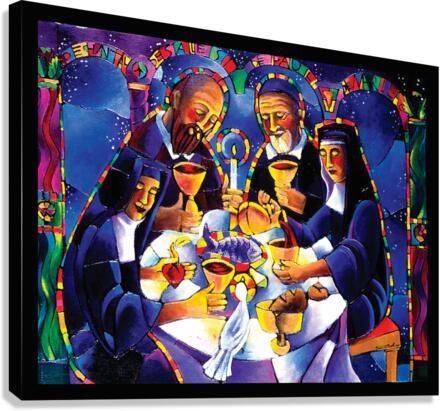

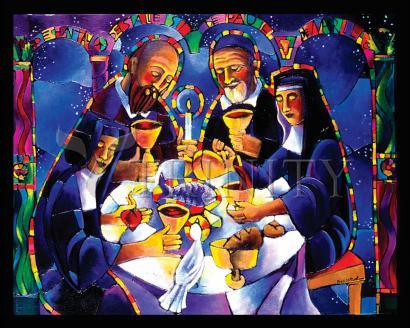

It is in the celebration of the Eucharist that this communion is most manifest. Here the whole church is united. The Eucharist binds Christians with the entire Christian community, living and dead, through those physically present at the celebration and those absent.

The Third Eucharistic Prayer prays that those who are nourished by the Lord's body and blood may be "filled with the Holy Spirit and become one body, one Spirit in Christ."

The other Eucharistic Prayers make it equally clear that Christians are bonded to one another in this communion of saints.

The Second Vatican Council re-emphasized this sense of community. In the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, we read: "All are joined together in Christ. So it is that the union of the wayfarers with the brothers and sisters who sleep in the peace of Christ is in no way interrupted but on the contrary, according to the constant faith of the church, this union is reinforced by an exchange of spiritual goods. Being more closely united with Christ, those who dwell in heaven consolidate the holiness of the whole church, add to the nobility of the worship that the church offers to God here on earth and in many ways help in a greater building up of the church. Once received into their heavenly home and being present to the Lord through him and with him and in him they do not cease to intercede with the Father for us as they proffer the merits which they acquired on earth through the one mediator between God and humanity, Christ Jesus."

This common fellowship makes up the body of Christ who is the ultimate holiness: the blessed in heaven, the suffering in purgatory and the militant on earth. There is an exchange of graces and blessings among them.

Pope Paul VI, in his encyclical Credo of the People of God, states: "The union of the pilgrims with the brethren who have gone to sleep in the peace of Christ is not in the least interrupted... Those in heaven place their merits at our disposal." This has been a most cherished and consoling teaching for Catholics.

The communion of saints brings together the present, past and future and makes sense of life. We have not lost those who have gone on before us. They are still there, though in a different form, and we still communicate with them.

We celebrate the feasts of All Saints and All Souls in November. In these feasts, we celebrate also the entry of our loved ones into heaven and look forward to the same thing happening to each of us.

Likewise, we celebrate the Assumption of Mary into heaven on August 15th. In Greek icons, the death of Mary is frequently depicted. We see her lying on her bed surrounded by the apostles. She falls asleep and is suddenly held, like a baby, in the arms of Jesus. Think of your beloved dead as being held in the arms of Jesus. They have moved from the faithful on earth to another dimension where they can intercede for their beloved here on earth.

We are all bound, as the poet says, "by gold chains about the feet of God" through our prayers for one another. We are members of a powerful, caring and everlasting assemblage -- the communion of saints.

"”Excerpts from "œCommunion of Saints" by Elizabeth McNamer