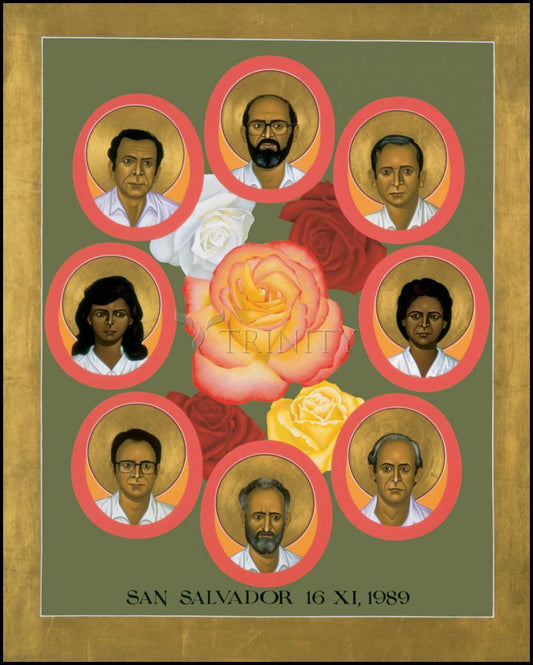

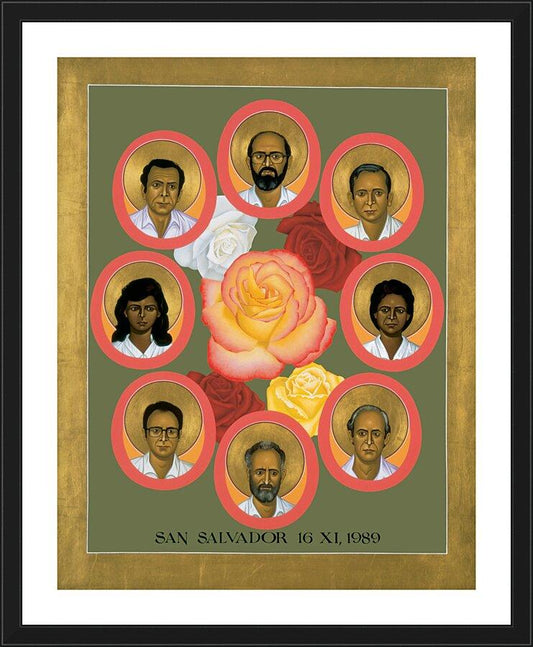

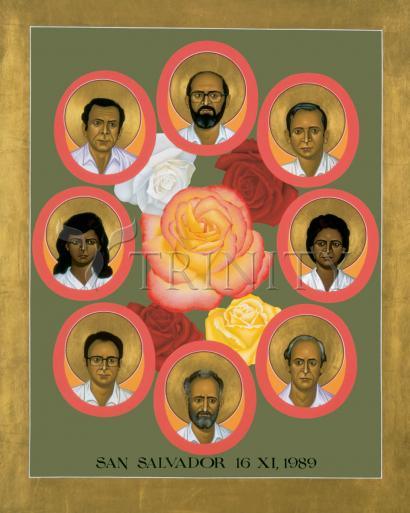

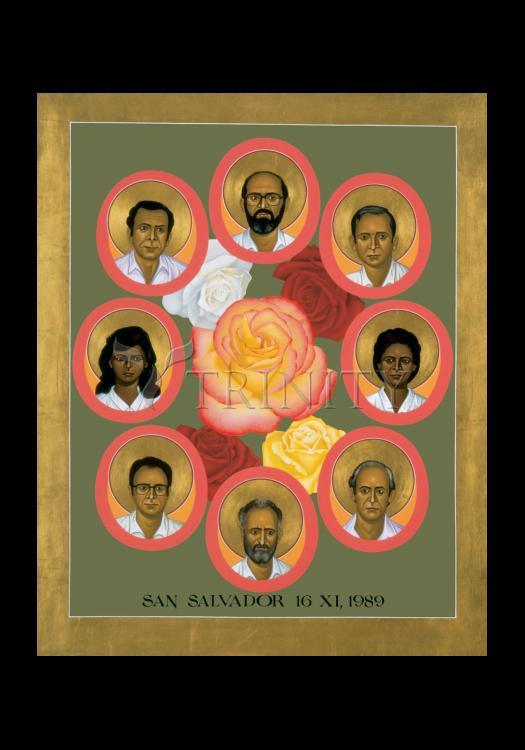

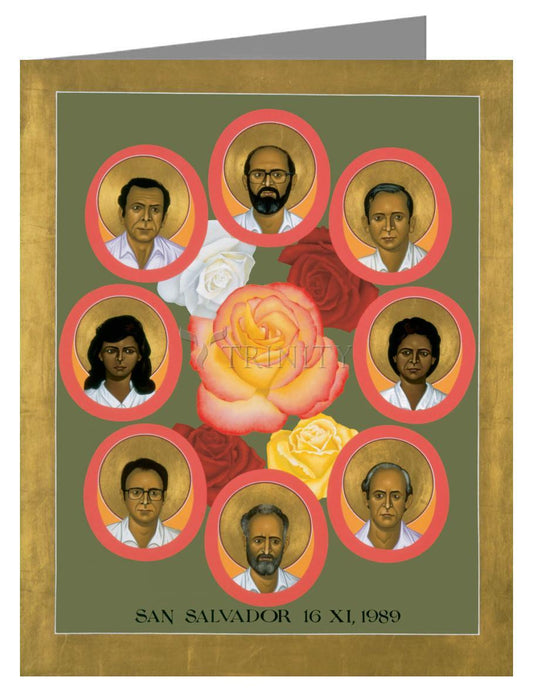

Before the end of darkness on the morning of Nov. 16, with unspeakable and barbaric cruelty, armed men burst into the Jesuit residence at the University of Central America in San Salvador and shot six Jesuit priests to death. At the same time, the community's cook and her daughter were murdered in their beds. According to reliable reports, several of the priests, my brothers, had their brains torn from their heads.

For a decade the people of El Salvador have suffered the effects of civil war. In recent days hundreds more have died in the seemingly senseless carnage. But the names of these latest victims are known to us quite personally. They include Ignacio Ellacuria, the rector (president) of the university, whose friendship I have treasured for six years. Fathers Segundo Montes and Ignacio Martin-Baro have been admired colleagues at Georgetown's Center for Immigration Policy and Refugee Assistance. The Jesuits' cook, Julia Elba Ramos, and her daughter Marisette were as precious in the eyes of God as any human being on Earth. If these Jesuits and their assistants can be murdered in cold blood, then anyone can be murdered.

And that, of course, is what we cry out against in our anguish. The human need to express outrage at such an evil signals our spirit's deepest conviction about justice and human dignity. Our all but mute grief mirrors a still deeper call to live life together in peace. We must believe that this call is stronger than our capacities for self-destruction. The tears we shed now are signs of a deeper power to bond us together as a human family.

For the dimensions of this tragedy are not only personal and political. If the fighting in the streets of San Salvador counts education and religious freedom among its casualties, we must decry an assault on the nation itself. Knowledge and faith belong to its soul. Whoever murders them, murders the country.

At Georgetown University, the blows struck Thursday morning of Nov. 16 have landed on our hearts. Twelve years ago my predecessor, Father Timothy Healy, journeyed with the president of the Jesuit Conference to San Salvador to award an honorary degree to Archbishop Oscar Arnulfo Romero. Two priests had recently been murdered, and Georgetown's degree was meant to show support for the archbishop and solidarity with the suffering of Salvadorans. A year later the university become a sister school of ours.

But two years later still, as all the world shudders to recall, Archbishop Romero was assassinated at the altar, his martyrdom since then a symbol comparable to Thomas a` Becket's in 1170 at Canterbury.

And so we beg for mercy. The most urgent need in El Salvador is for a cease-fire such as been recommended by the Catholic Church there. Only a cease-fire and a reopening of the peace talks can reestablish an initial degree of order. The government's overwhelming military power must not be used simply to exterminate the rebel forces.

Further, the International Red Cross should be allowed to enter the city. Currently, food, water and medical supplies are lacking for many wounded and dying people, especially civilians. Respect must be shown for the parishes that the Catholic Church has established as hospitals or as sanctuaries for civilians. And, of course, the crime at the university must be investigated and the perpetrators brought to justice. Our own government should be involved in pressing the peace process forward and urging the government of El Salvador to draw mercy from this latest martyrdom.

I have appealed to President Alfredo Cristiani, a graduate of Georgetown, to consider these measures. With the assistance of James Cardinal Hickey, I have gathered a group of ecumenical religious leaders and educators to approach our government and consider what we can and should do for the people of El Salvador.

Our human history is a long story of suffering. For centuries it has stood inescapably under the sign of the cross of Jesus of Nazareth. It stands now under the signs of Auschwitz and Hiroshima. But we cannot believe that it is only the annals of atrocity. We must give every effort of our hearts and minds to draw light from the darkness of nights like that of Nov. 16.

"By Leo J. O'Donovan, S.J. President, Georgetown University, Sunday, November 19, 1989; Page D07, Washington Post