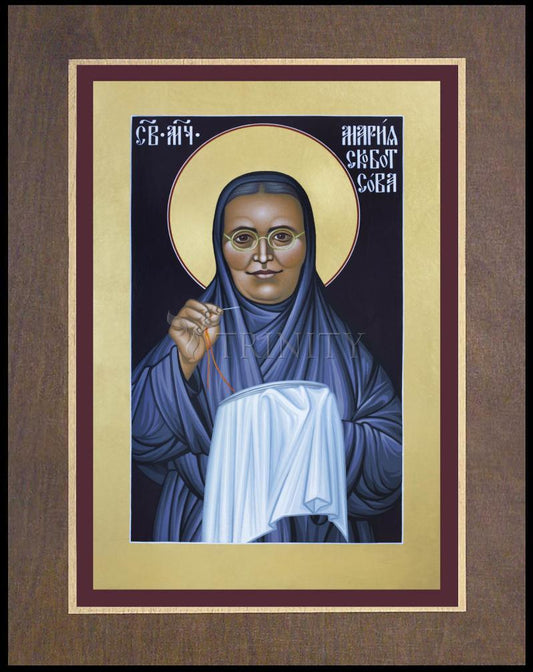

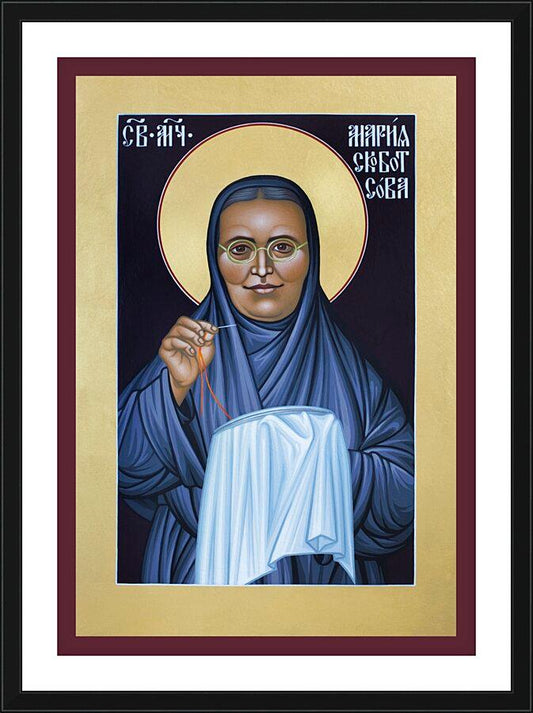

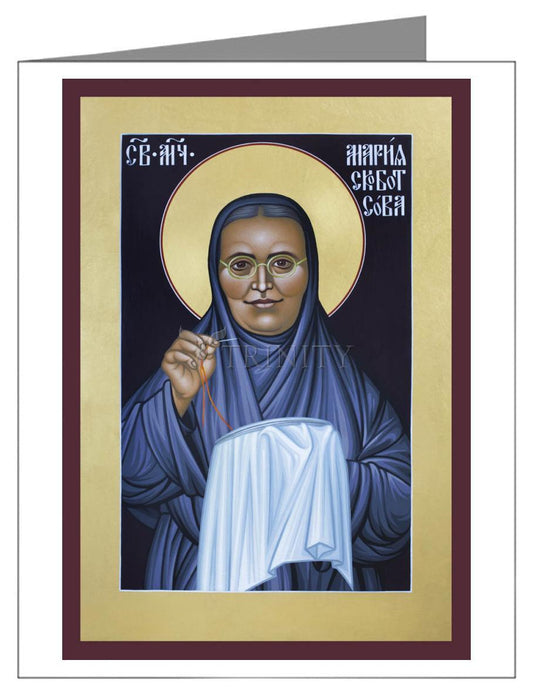

On January 18, 2004, the Holy Synod of the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Istanbul recognized Mother Maria Skobtsova as a saint along with her son Yuri, the priest who worked closely with her, Fr. Dimitri Klépinin, and her close friend and collaborator Ilya Fondaminsky. All four died in German concentration camps.

"No amount of thought will ever result in any greater formulation than the three words, 'Love one another,' so long as it is love to the end and without exceptions."

Those who know the details of her life tend to regard Mother Maria Skobtsova as one of the great saints of the twentieth century: a brilliant theologian who lived her faith bravely in nightmarish times, finally dying a martyr's death at the Ravensbruck concentration camp in Germany in 1945.

Elizaveta Pilenko, the future Mother Maria, was born in 1891 in the Latvian city of Riga, then part of the Russian Empire, and grew up in the south of Russia on a family estate near the town of Anapa on the shore of the Black Sea. In her family she was known as Liza. For a time her father was mayor of Anapa. Later he was director of a botanical garden and school at Yalta. On her mother's side, Liza was descended from the last governor of the Bastille, the Parisian prison destroyed during the French Revolution.

Her parents were devout Orthodox Christians whose faith helped shape their daughter's values, sensitivities and goals. As a child she once emptied her piggy bank in order to contribute to the painting of an icon that would be part of a new church in Anapa. At seven she asked her mother if she was old enough to become a nun, while a year later she sought permission to become a pilgrim who spends her life walking from shrine to shrine. (As late as 1940, when living in German-occupied Paris, thoughts of one day being a wandering pilgrim and missionary in Siberia again filled her imagination.)

When she was fourteen, her father died, an event which seemed to her meaningless and unjust and led her to atheism. "If there is no justice," she said, "there is no God." She decided God's nonexistence was well known to adults but kept secret from children. For her, childhood was over.

When her widowed mother moved the family to St. Petersburg in 1906, she found herself in the country's political and cultural center " also a hotbed of radical ideas and groups.

She became part of radical literary circles that gathered around such symbolist poets as Alexander Blok, whom she first met at age fifteen. Blok responded to their unexpected meeting " Liza had come to visit unannounced " with a poem that included the lines:

Only someone who is in love

Has the right to call himself a human being.

In a note that came with the poem, Blok told Liza that many people were dying where they stood. The world-weary poet urged her "to run, run from us, the dying ones." She replied with a vow fight "against death and against wickedness."

Like so many of her contemporaries, she was drawn to the left, but was often disappointed that the radicals she encountered. Though regarding themselves as revolutionaries, they seemed to do nothing but talk. "My spirit longed to engage in heroic feats, even to perish, to combat the injustice of the world," she recalled. Yet no one she knew was actually laying down his life for others. Should her friends hear of someone dying for the Revolution, she noted, "they will value it, approve or not approve, show understanding on a very high level, and discuss the night away till the sun rises and it's time for fried eggs. But they will not understand at all that to die for the Revolution means to feel a rope around one's neck."

Liza began teaching evening courses to workers at the Poutilov Plant, but later gave it up in disillusionment when one of her students told her that he and his classmates weren't interested in learning as such, but saw classes as a necessary path to becoming clerks and bureaucrats. The teen-age Liza wanted her workers to be every bit as idealistic as she was.

In 1910, Liza married Dimitri Kuzmin-Karaviev, a member of Social Democrat Party, better known as the Bolsheviks. She was eighteen, he was twenty-one. It was a marriage born "more of pity than of love," she later commented. Dimitri had spent a short time in prison several years before, but by the time of their marriage was part of a community of poets, artists and writers in which it was normal to rise at three in the afternoon and talk the night through until dawn.

She not only knew poets but wrote poems in the symbolist mode. In 1912 her first collection of poetry, "Scythian Shards", was published.

Like many other Russian intellectuals, she later reflected, she was a participant in the revolution before the Revolution that was "so deeply, pitilessly and fatally laid over the soil of old traditions" only to destroy far more than it created. "Such courageous bridges we erected to the future! At the same time, this depth and courage were combined with a kind of decay, with the spirit of dying, of ghostliness, ephemerality. We were in the last act of the tragedy, the rupture between the people and the intelligentsia."

She and her friends also talked theology, but just as their political ideas had no connection at all to the lives of ordinary people, their theology floated far above the actual Church. There was much they might have learned, she reflected later in life, from "any old beggar woman hard at her Sunday prostrations in church." For many intellectuals, the Church was an idea or a set of abstract values, not a community in which one actually lives.

Though still regarding herself as an atheist, little by little her earlier attraction to Christ revived and deepened, not yet Christ as God incarnate but Christ as heroic man. "Not for God, for He does not exist, but for the Christ," she said. "He also died. He sweated blood. They struck His face " [while] we pass by and touch His wounds and yet are not burned by His blood."

One door opened to another. Liza found herself drawn toward the religious faith she had jettisoned after her father's death. She prayed and read the Gospel and the lives of saints. It seemed to her that the real need of the people was not for revolutionary theories but for Christ. She wanted "to proclaim the simple word of God," she told Blok in a letter written in 1916. The same year her second collection of poems, "Ruth", appeared in St. Petersburg.

Deciding to study theology, she applied for entrance at the Theological Academy of the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in St. Petersburg, in those days an entirely male school whose students were preparing for ordination as priests. As surprising as her wanting to study there was the rector's decision that she could be admitted.

By 1913, Liza's marriage collapsed. (Later in his life Dimitri became a Christian, joined the Catholic Church, and later lived and worked among Jesuits in western Europe.) That October her first child, Gaiana, was born.

Just as World War I was beginning, Liza returned with her daughter to her family's country home near Anapa in Russia's deep south. Her religious life became more intense. For a time she secretly wore lead weights sewn into a hidden belt as a way of reminding herself both "that Christ exists" and also to be more aware that minute-by-minute many people were suffering and dying in the war. She realized, however, that the primary Christian asceticism was not self-mortification, but caring response to the needs of other people while at the same time trying to create better social structures. She joined the ill-fated Social Revolutionary Party, a movement that, despite the contrast in names, was far more democratic than Lenin's Social Democratic Party.

On a return visit to St. Petersburg, Liza spent hours visiting a small chapel best known for a healing icon in which small coins had been embedded when lightning struck the poor box that stood nearby " it was called the Mother of God, Joy of the Sorrowful, with Kopeks. Here she prayed in a dark corner, reviewing her life as one might prepare for confession, finally feeling God's overwhelming presence. "God is over all," she knew with certainty, "unique and expiating everything."

In October 1917, Liza was present in St. Petersburg when Russia's Provisional Government was overthrown by the Bolsheviks. Taking part in the All-Russian Soviet Congress, she heard Lenin's lieutenant, Leon Trotsky, dismiss people from her party with the words, "Your role is played out. Go where you belong, into history's garbage can!"

On the way home, she narrowly escaped summary execution by convincing a Bolshevik sailor that she was a friend of Lenin's wife. It was on that difficult journey of many train rides and long waits at train stations that she began to see the scale of the catastrophe Russia was now facing: terror, random murder, massacres, destroyed villages, the rule of hooligans and thugs, hunger and massive dislocation. How hideously different actual revolution was from the dreams of revolution that had once filled the imagination of so many Russians, not least the intellectuals!

In February 1918, in the early days of Russia's Civil War, Liza was elected deputy mayor of Anapa. She hoped she could keep the town's essential services working and protect anyone in danger of the firing squad. "The fact of having a female mayor," she noted, "was seen as something obviously revolutionary." Thus they put up with "views that would not have been tolerated from any male."

She became acting mayor after the town's Bolshevik mayor fled when the White Army took control of the region. Again her life was in danger. To the White forces, Liza looked as Red as any Bolshevik. She was arrested, jailed, and put on trial for collaboration with the enemy. In court, she rose and spoke in her own defense: "My loyalty was not to any imagined government as such, but to those whose need of justice was greatest, the people. Red or White, my position is the same " I will act for justice and for the relief of suffering. I will try to love my neighbor."

It was thanks to Daniel Skobtsov, a former schoolmaster who was now her judge, that Liza avoided execution. After the trial, she sought him out to thank him. They fell in love and within days were married. Before long Liza found herself once again pregnant.

The tide of the civil war was now turning in favor of the Bolsheviks. Both Liza and her husband were in peril, as well as her daughter and unborn child. They made the decision many thousands were making: it was safest to go abroad. Liza's mother, Sophia, came with them.

Their journey took them across the Black Sea to Georgia in the putrid hold of a storm-beaten steamer. Liza's son Yura was born in Tbilisi in 1920. A year later they left for Istanbul and from there traveled to Yugoslavia where Liza gave birth to Anastasia, or Nastia as she was called in the family. Their long journey finally ended final in France. They arrived in Paris in 1923. Friends gave them use of a room. Daniel found work as a part-timer teacher, though the job paid too little to cover expenses. To supplement their income, Liza made dolls and painted silk scarves, often working ten or twelve hours a day.

A friend introduced her to the Russian Student Christian Movement, an Orthodox association founded in 1923. Liza began attending lectures and taking part in other activities of the group. She felt herself coming back to life spiritually and intellectually.

In the hard winter of 1926, each person in the family came down with influenza. All recovered except Nastia, who became thinner with each passing day. At last a doctor diagnosed meningitis. The Pasteur Institute accepted Nastia as a patient, also giving permission to Liza to stay day and night to help care for her daughter.

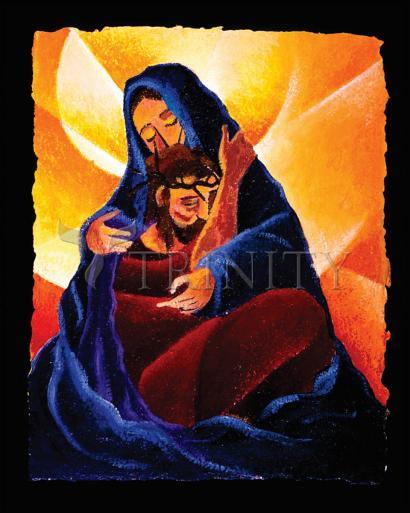

Liza's vigil was to no avail. After a month in the hospital, Nastia died. Even then, for a day and night, her grief-stricken mother sat by Nastia's side, unable to leave the room. During those desolate hours, she came to feel how she had never known "the meaning of repentance, but now I am aghast at my own insignificance ". I feel that my soul has meandered down back alleys all my life. And now I want an authentic and purified road. Not out of faith in life, but in order to justify, understand and accept death ". No amount of thought will ever result in any greater formulation than the three words, 'Love one another,' so long as it is love to the end and without exceptions. And then the whole of life is illumined, which is otherwise an abomination and a burden."

The death of someone you love, she wrote, "throws open the gates into eternity, while the whole of natural existence has lost its stability and its coherence. Yesterday's laws have been abolished, desires have faded, meaninglessness has displaced meaning, and a different, albeit incomprehensible Meaning, has caused wings to sprout on one's back ". Before the dark pit of the grave, everything must be reexamined, measured against falsehood and corruption."

After her daughter's burial, Liza became "aware of a new and special, broad and all-embracing motherhood." She emerged from her mourning with a determination to seek "a more authentic and purified life." She felt she saw a "new road before me and a new meaning in life, to be a mother for all, for all who need maternal care, assistance, or protection."

Liza devoted herself more and more to social work and theological writing with a social emphasis. In 1927 two volumes, Harvest of the Spirit, were published in which she retold the lives of many saints.

In the same period, her husband began driving a taxi, a job which provided a better income than part-time teaching. By now Gaiana was living at a boarding school in Belgium, thanks to help from her father. But Liza and Daniel's marriage was dying, perhaps a casualty of Nastia's death.

Feeling driven to devote herself as fully as possible to social service, Liza, with her mother, moved to central Paris, thus closer to her work. It was agreed that Yura would remain with his father until he was fourteen, though always free to visit and stay with his mother until he was fourteen, when he would decide for himself with which parent he would live. (In fact Yura, found to be in the early stages of tuberculosis, was to spend a lengthy period in a sanatarium apart from both parents.)

In 1930, the same year her third book of poetry was published, Liza was appointed traveling secretary of the Russian Student Christian Movement, work which put her into daily contact with impoverished Russian refugees in cities, towns and villages throughout France and sometimes in neighboring countries.

She made her monastic profession, Metropolitan Eulogy recognized, "in order to give herself unreservedly to social service." Mother Maria called it simply "monasticism in the world."

Her credo was: "Each person is the very icon of God incarnate in the world." With this recognition came the need "to accept this awesome revelation of God unconditionally, to venerate the image of God" in her brothers and sisters.

She enjoyed a legend concerning two fourth-century saints, Nicholas of Myra and John Cassian, who returned to earth to see how things were going. They came upon a peasant, his cart mired in the mud, who begged their help. John Cassian regretfully declined, explaining that he was soon due back in heaven and therefore must keep his robes spotless. Meanwhile Nicholas was already up to his hips in the mud, freeing the cart. When the Ruler of All discovered why Nicholas was caked in mud and John Cassian immaculate, it was decided that Nicholas' feast day would henceforth be celebrated twice each year " May 9 and December 6 " while John Cassian's would occur only once every four years, on February 29.

Mother Maria felt sustained by the opening verses of the Sermon on the Mount: "Not only do we know the Beatitudes, but at this hour, this very minute, surrounded though we are by a dismal and despairing world, we already savor the blessedness they promise""

It was no virtue of her own that could account for her activities, she insisted. "There is no hardship in it, since all the relief comes my way. God having given me a compassionate nature, how else could I live?"

"It is not enough to give," Mother Maria might say. "We must have a heart that gives." If mistakes were made, if people betrayed a trust, the cure was not to limit giving. "The only ones who make no mistakes," she said, "are those who do nothing."

Mother Maria and her collaborators would not simply open the door when those in need knocked, but would actively seek out the homeless. One place to find them was an all-night café at Les Halles where those with nowhere else to go could sit as long as they liked for the price of a glass of wine. Children were also cared for. A part-time school was opened at several locations.

Fortunately for the community, their prudent business manager, Fedor Pianov, formerly general secretary of the Russian Christian Student Movement, at times intervened in cases where a trusted person was systematically violating the confidence placed in him, as sometimes happened.

Turning her attention toward Russian refugees who had been classified insane, Mother Maria began a series of visits to mental hospitals. In each hospital five to ten percent of the Russian patients turned out to be sane and, thanks to her intervention, were released. Language barriers and cultural misunderstandings had kept them in the asylum.

An inquiry into the needs of impoverished Russians suffering from tuberculosis resulted in the opening in 1935 of a sanatorium in Noisy-le-Grand. Its church was a former hen house. Her efforts bore the unexpected additional fruit of other French TB sanatoria opening their doors to Russian refugees. The house at Noisy, no longer having to serve its original function, then became a rest home. It was here that Mother Maria's mother Sophia ended her days in 1962. She was a century old.

Controversial in life, Mother Maria remains a subject of contention to this day, a fact which may explain the slowness of the Orthodox Church in adding her to the calendar of saints. While clearly she lived a life of heroic virtue and is among the martyrs of the twentieth century, her verbal assaults on nationalistic and tradition-bound forms of religious life still raise the blood pressure of many Orthodox Christians. Mother Maria remains an indictment of any form of Christianity that seeks Christ chiefly inside church buildings.

"Excerpts from "In Communion" website of the Orthodox Peace Fellowship

Born:1891

Died: Mother Maria was sent to the Ravensbrück concentration camp. On Holy Saturday, 1945, she took the place of a Jewish woman who was going to be sent to the Gas Chamber, and died in her place.

Canonized: January 16, 2004