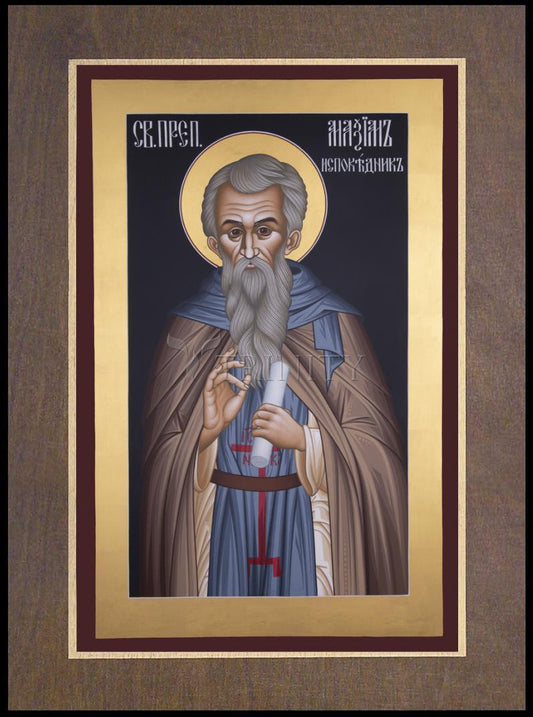

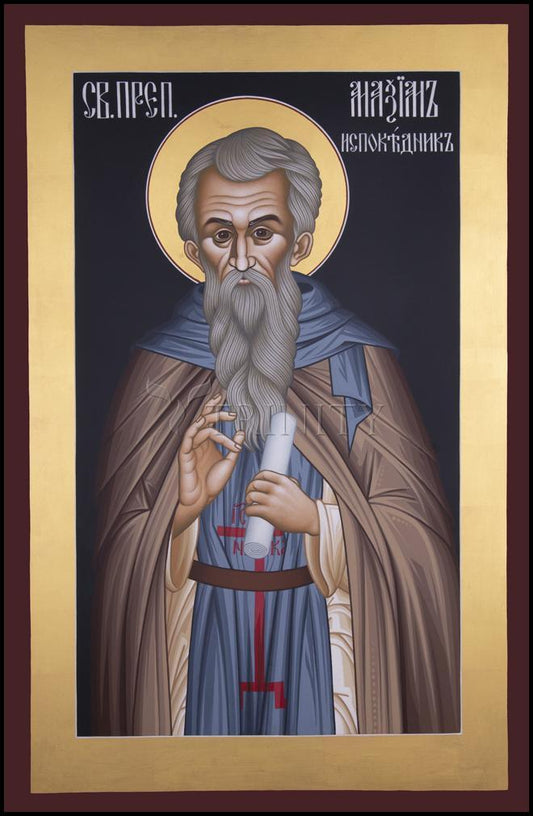

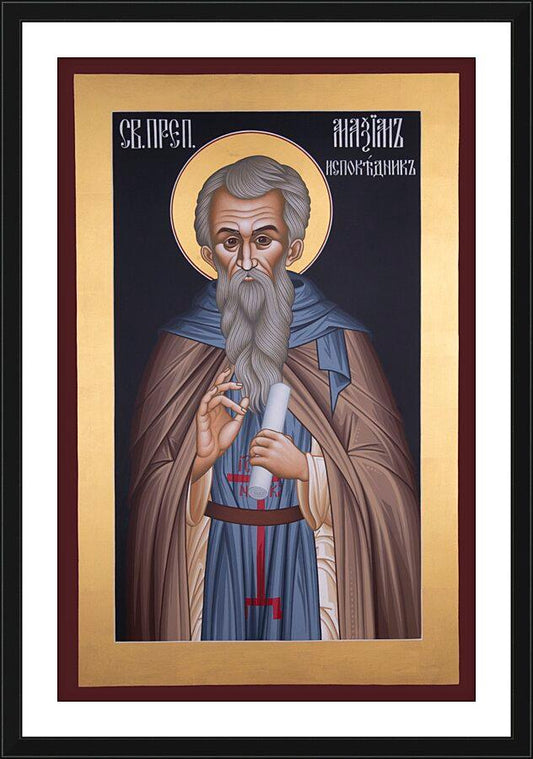

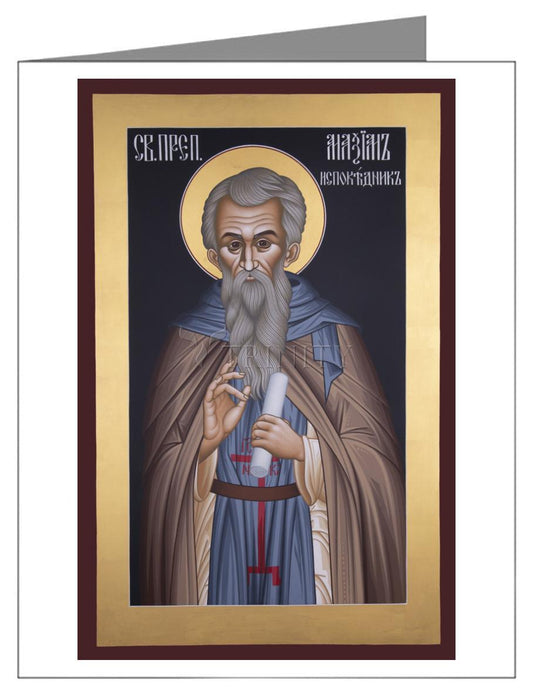

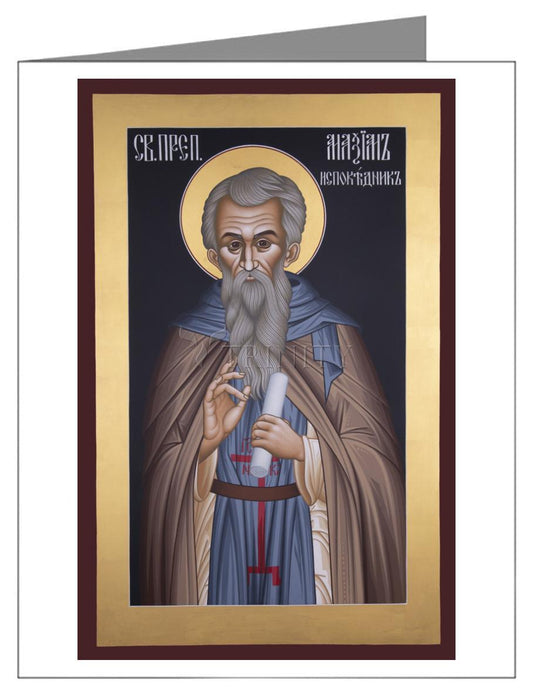

St Maximus the Confessor

Maximos had one of the greatest minds in the history of the church.Born in 580 in Constantinople, he was an aristocrat who became an official in the court of Emperor Heraclius, but left to enter the monastery.

In an age when theology dominated public thinking, Maximos rose to the occasion.He responded to a strange movement called monothelitism. The monothelites held that Christ, while both human and divine, had only one will, that of the Father.Maximos defended the church's teaching that Jesus Christ had both a human and a divine will.Anything else would make Christ a freak, not a human being, and he must be fully human, otherwise how could his life, death, and resurrection connect with other humans?

The saying of the fathers was, "what is not assumed cannot be saved."Because we are alienated from God through sin, Christ took up our total human nature " body, soul, will, reason, intellect, all that we are as humans " and joined it once again to God. By this voluntary co-operation of Man with God in Christ, the integrity of human nature is restored. Our human will can act in concert with God's will " just as we see in Christ " so that we "live for the rest of the time"no longer by human passions but by the will of God" (I Peter 4:2).Through the new Adam we gain by grace what the old Adam lost by nature.

Maximos wanted to safeguard this faith that we become "partakers in divine nature" (II Peter 1:4), which would be impossible, if the monothelites were correct.Unfortunately, the Emperor and even the Patriarch of Constantinople did not see the error in the monothelite view.At this crucial juncture in church history, Maximos stood virtually alone.His arguments proved so convincing, however, that the Patriarch reversed his position in 645 and returned to the Orthodox Catholic faith.

His opponents were ruthless. Maximos was hounded out of town, beaten and eventually his enemies severed his hand to stop his writing and cut his tongue to stop his speaking.His scribe continued to write for him after this.

St Maximos died 13 August 662.His writings on liturgy, devotion, ascetic practice, and theology continue to circulate.He was one of the brilliant lights in what we call "the dark ages," and he was vindicated in 680 when the Sixth Ecumenical Council officially condemned monothelitism.