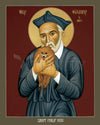

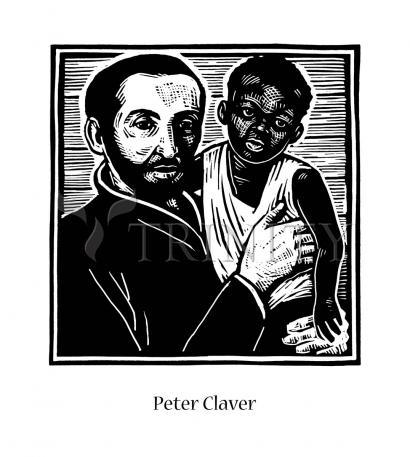

Collection: St. Peter Claver

-

Sale

Wood Plaque Premium

Regular price From $99.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$111.06 USDSale price From $99.95 USDSale -

Sale

Wood Plaque

Regular price From $34.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$38.83 USDSale price From $34.95 USDSale -

Sale

Wall Frame Espresso

Regular price From $109.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$122.17 USDSale price From $109.95 USDSale -

Sale

Wall Frame Gold

Regular price From $109.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$122.17 USDSale price From $109.95 USDSale -

Sale

Wall Frame Black

Regular price From $109.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$122.17 USDSale price From $109.95 USDSale -

Sale

Canvas Print

Regular price From $84.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$94.39 USDSale price From $84.95 USDSale -

Sale

Metal Print

Regular price From $94.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$105.50 USDSale price From $94.95 USDSale -

Sale

Acrylic Print

Regular price From $94.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$105.50 USDSale price From $94.95 USDSale -

Sale

Giclée Print

Regular price From $19.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$22.17 USDSale price From $19.95 USDSale -

Custom Text Note Card

Regular price From $300.00 USDRegular priceUnit price per$333.33 USDSale price From $300.00 USDSale

ARTIST: Julie Lonneman

ARTWORK NARRATIVE:

Young Jesuit Peter Claver left Spain in 1610 for the colonies of the New World. He was ordained in Cartagena (Columbia) in 1615 and never returned to his native land.

Cartagena, a bustling port on the Caribbean, was a major center for the slave trade. Ten thousand slaves arrived each year, disembarking from ships in which conditions were so horrendous that an estimated one-third of the slaves died while crossing the Atlantic. Peter Claver met the arriving slave ships and entered their putrid holds bearing medicines, food, brandy, lemons and tobacco. His assistance was not limited to the physical: Claver instructed and baptized an estimated 300,000 slaves during the 40 years of his ministry. But he would often say, "We must speak to them with our hands before we try to speak to them with our lips.”

Though Claver declared himself "the slave of the Negroes forever,” and devoted himself tirelessly to their wellbeing, his care extended to all the people of Cartagena. He could be found preaching in the city square and giving missions to sailors and traders. When traveling on mission trips in the countryside, he refused the hospitality of slave owners, instead insisting on lodging in the slave quarters.

His feast day is September 9.

- Art Collection:

-

Saints & Angels

- Patronage:

-

Slavery,

-

Race Relations,

-

Inter-racial Justice,

-

Foreign Missions,

-

Colombia,

-

Black People,

-

Black Missions,

-

African-Americans,

-

African Missions

- Lonneman collection:

-

Models of Faith

The son of a Catalonian farmer, Peter was born at Verdu, in 1581. He died 8 September, 1654. He obtained his first degrees at the University of Barcelona. At the age of twenty he entered the Jesuit novitiate at Tarragona. While he was studying philosophy at Majorca in 1605, Alphonsus Rodriguez, the saintly doorkeeper of the college, learned from God the future mission of his young associate, and thenceforth never ceased exhorting him to set out to evangelize the Spanish possessions in America.

Peter obeyed, and in 1610 landed at Cartagena, where for forty-four years he was the Apostle of the negro slaves. Early in the seventeenth century the masters of Central and South America afforded the spectacle of one of those social crimes which are entered upon so lightly. They needed laborers to cultivate the soil which they had conquered and to exploit the gold mines. The natives being physically incapable of enduring the labors of the mines, it was determined to replace them with negroes brought from Africa.

The coasts of Guinea, the Congo, and Angola became the market for slave dealers, to whom native petty kings sold their subjects and their prisoners. By its position in the Caribbean Sea, Cartagena became the chief slave-mart of the New World. A thousand slaves landed there each month. They were bought for two or so, and sold for 200 écus.

Though half the cargo might die, the trade remained profitable. Neither the repeated censures of the pope, nor those of Catholic moralists could prevail against this cupidity. The missionaries could not suppress slavery, but only alleviate it, and no one worked more heroically than Peter Claver.

Trained in the school of Père Alfonso de Sandoval, a wonderful missionary, Peter declared himself the slave of the negroes forever, and thenceforth his life was one that confounds egotism by its superhuman charity. Although timid and lacking in self- confidence, he became a daring and ingenious organizer. Every month when the arrival of the negroes was signaled, Claver went out to meet them on the pilot's boat, carrying food and delicacies.

The negroes, cooped up in the hold, arrived crazed and brutalized by suffering and fear. Claver went to each, cared for him, and showed him kindness, and made him understand that henceforth he was his defender and father. He thus won their good will. To instruct so many speaking different dialects, Claver assembled at Cartagena a group of interpreters of various nationalities, of whom he made catechists. While the slaves were penned up at Cartagena waiting to be purchased and dispersed, Claver instructed and baptized them in the Faith.

On Sundays during Lent he assembled them, inquired concerning their needs, and defended them against their oppressors. This work caused Claver severe trials, and the slave merchants were not his only enemies. The Apostle was accused of indiscreet zeal, and of having profaned the Sacraments by giving them to creatures who scarcely possessed a soul. Fashionable women of Cartagena refused to enter the churches where Father Claver assembled his negroes. The saint's superiors were often influenced by the many criticisms which reached them.

Nevertheless, Claver continued his heroic career, accepting all humiliations and adding rigorous penances to his works of charity. Lacking the support of men, the strength of God was given him. He became the prophet and miracle worker of New Granada, the oracle of Cartagena, and all were convinced that often God would not have spared the city save for him. During his life he baptized and instructed in the Faith more than 300,000 negroes.. His feast is celebrated on the ninth of September. On 7 July, 1896, he was proclaimed the special patron of all the Catholic missions among the negroes.

Born: 1581 at Verdu, Catalonia, Spain

Died: September 8, 1654 at Cartegena, Colombia of natural causes.

Canonized: January 15, 1888 by Pope Leo XIII

Also known as: Slave of the Blacks; Slave of the Slaves

Readings:

To love God as He ought to be loved, we must be detached from all temporal love. We must love nothing but Him, or if we love anything else, we must love it only for His sake.

—Saint Peter Claver

St. Peter Claver, S.J. (1581-1654) was unable to abolish the slave trade, but he did what he could to mitigate its horrors, once the slaves arrived in the New World, by bringing them the consolations of religion and ministering to their bodily wants. He landed in Cartagena in 1610 and for forty years strove to alleviate their lot, with true apostolic fervor, declaring himself "the slave of the Negroes forever."

Cartagena, which was founded by Pedro de Heredia in 1533, owed its great commercial importance to its superb harbor. It is situated in the Caribbean Sea near the most northerly point of South America, to the east of the Isthmus of Panama. It is in the tropics, about 700 miles north of the Equator.

When Peter Claver first set foot in Cartagena, he kissed the ground which was to be the scene of his future labors. He had every reason to rejoice, for the climate of Cartagena was disagreeably hot and moist, the country around was flat and marshy, the soil was barren, the necessities of life had to be imported, and in the time of Peter Claver fresh vegetables were almost unknown. In the seventeenth century Cartagena was the happy hunting ground of fever-bearing insects from tropical swamps.

These, the natural disadvantages of Cartagena, might have been wasted on a robust saint, but Claver must have been consoled to feel that the fine edge of these discomforts would not be blunted by a naturally healthy constitution. He had, indeed, been warned that delicate health might easily succumb to excessive heat.

Cartagena was the chief center for the slave trade. Slave-traders picked up slaves at four crowns a head on the coast of Guinea or Congo, and sold them for 200 crowns or more at Cartagena. The voyage lasted two months, slaves cannot live on air, even foul air, and the overheads may fairly be credited with 33 per cent or so of slaves who died en route.

Father Claver, whose life's work was to be the instruction, the conversion and the care of the Negroes who landed in Cartagena, began his ministry under the guidance of Father Alfonso de Sandoval.

Father Claver never experienced that momentary weakness which always overcame the heroic Sandoval when a slave ship was announced. The horror with which Sandoval contemplated a return to these scenes of squalid misery only serves to increase our admiration of the courage with which he conquered these very natural shrinkings of the flesh.

Father Claver, on the other hand, was transported with joy when messengers announced the arrival of a fresh cargo of Africans. Indeed, he bribed the officials of Cartagena with the promise to say Mass for the intentions of whoever was first to bring him this joyful news. But there was no need for such bribes, for among the simple pleasures of life must be counted the happiness of bringing good news to a grateful recipient. The Governor himself coveted this mission, for the happiness of watching the radiant dawn of joy on the saint's face. At the words "Another slave ship" his eyes brightened, and color flooded back into his pale, emaciated cheeks.

In the intervals between the arrival of slave ships, Father Claver wandered round the town with a sack. He went from house to house, begging for little comforts for the incoming cargo. Claver enjoyed the respect of the responsible officials of the Crown in Cartagena, devout Catholics who approved warmly the work of instruction which the good Father carried on amongst the Negroes. They felt this responsibility for the welfare of these exiles. Such opposition as Claver encountered amongst the Spaniards came from the traders and planters, who were often inconvenienced by Claver's zeal on behalf of his black children.

The black cargo arrived in a condition of piteous terror. They were convinced that they were to be bought by merchants who needed their fat to grease the keels of ships, and their blood to dye the sails, for this was one of the favorite bedtime stories with which they had been regaled by friendly mariners during the two months' passage. The first appearance of Father Claver was often greeted with screams of terror, but it was only a matter of moments to convince these frantic creatures that Claver was no purchaser of slave fat and slave blood.

He scarcely needed the interpreters who accompanied him for this purpose for the language of love survived in the confusion of Babel, and readily translated itself into gesture. Long before the interpreters had finished explaining that the story which had so terrified them was the invention of the devil, Father Claver had already soothed and comforted them by his very presence. And not only by his presence, for Claver was a practical evangelist. The biscuits, brandy, tobacco and lemons which he distributed were practical tokens of friendship. "We must," he said, "speak to them with our hands, before we try to speak to them with our lips."

After a brief talk to the Negroes on deck, Claver descended to the sick between decks. In this work he was often alone. Many of his African interpreters were unable to endure the stench and fainted at the first contact with that appalling atmosphere. Claver, however, did not recoil. Indeed, he regarded this part of his work as of special importance. Again and again he was able to impart to some poor dying wretch those elements of Christian truth which justified him in administering baptism.

It is recorded that the person of Father Claver was sometimes illumined with rays of glory as he passed through the hospital wards of Cartagena. It may well be that a radiance no less illuminating lit the dark bowels of the slave ship as Father Claver moved among the dying. There they lay in the slime, the stench and the gloom, their bodies still bleeding from the lash, their souls still suffering from insults and contempt.

There they lay, and out of the depths called upon the tribal gods who had deserted them, and called in vain. Then suddenly things changed. The dying Africans saw a face bending over them, a face illumined with love, and a voice infinitely tender, and the deft movement of kind hands easing their tortured bodies, and supreme miracle his lips meeting their filthy sores in a kiss... A love so divine was an unconquerable argument for the God in whom Father Claver believed.

When Father Claver returned next day he was welcomed with ecstatic cries of child-like affection. Two or three days usually passed before arrangements at the port could be completed to allow the disembarkation of a fresh cargo of slaves. When the day of disembarkation arrived, Father Claver was always present, waiting on shore with another stock of provisions and delicacies. Sometimes he would carry the sick ashore in his own arms.

Again and again in the records of his mission, we find evidences of his strength, which seemed almost supernatural. His diet would have been ridiculously inadequate for a normal man living a sedentary life. His neglect of sleep would have killed a normal man within a few years, but in spite of his contempt for all ordinary rules of health, in spite of a constitution which was none too strong at the outset of his career, he proved himself capable of outworking and out-walking and out-nursing all his colleagues. He made every effort to secure for the sick special carts, as otherwise they ran the risk of being driven forward under the lash. He did not leave them until he had seen them to their lodgings, and men said that Father Claver escorting slaves back to Cartagena reminded them of a conqueror entering Rome in triumph.

It was after the Negroes had been lodged in the magazines where they awaited their sale and ultimate disposal that Claver's real work began. In the case of the dying, Claver was satisfied if he could awaken some dim sense of contrition of sin, and some faint glimmering of understanding of the fundamental Christian belief. The healthy slaves, however, had to qualify by a course of rigid instruction for the privilege of baptism.

I have already referred to the crowded conditions of the compound in which the Negroes were stocked on disembarkation, and on the squalor and misery which was the result of the infectious diseases from which many of them were suffering. The stink of sick Negroes, confined in a limited space, often proved insupportable to Father Claver's Negro interpreters. It was in this noxious and empoisoned air that Peter Claver's greatest work was achieved.

Before the day's work began, Father Claver prepared himself by special prayers before the Blessed Sacrament and by self-inflicted austerities. He then passed through the streets of Cartagena, accompanied by his African interpreters, and bearing a staff crowned by a cross. On his shoulder he carried a bag which contained his stole and surplice, the necessities for the arrangement of an altar, and his little store of comforts and delicacies. Heavily loaded though he was, his companions found it difficult to keep up with this eager little man who dived through the crowded streets with an enthusiasm which suggested a lover hurrying to a trysting place.

On arrival, his first care was for the sick. He had a delicacy of touch in the cleansing and dressing of sores which was a true expression of his personality. After he had made the sick comfortable on their couches and given them a little wine and brandy and refreshed them with scented water, he then proceeded to collect the healthier Negroes into an open space.

In his work of instruction Claver relied freely on pictures. This method appealed effectively to the uneducated mind, and was, moreover, in accordance with the teachings of his Order, for, as we have seen, St. Ignatius in his Spiritual Exercises was constant in urging the exercitant to picture to himself sensibly the subject matter of his meditations. His favorite picture was in the form of a triptych, in the center Christ on the Cross, his precious blood flowing from each wound into a vase, below the Cross a priest collecting this blood to baptize a faithful Negro. On the right side of the triptych a naively dramatic group of Negroes, glorious and splendidly arrayed; on the left side the wicked Negroes, hideous and deformed, surrounded by unlovely monsters.

Claver was particularly careful to make every possible arrangement for the comfort of his catechumens. He himself remained standing, even in the heat of the day, and the slave-masters, who sometimes attended these edifying ceremonies, often remonstrated with the slaves for remaining seated while their instructor stood. But Father Claver always intervened, and explained with great earnestness to the slave-masters that the slaves were the really important people at this particular performance, and that he himself was a mere cypher who was there for their convenience.

Sometimes, if a Negro was so putrescent with sores as to be revolting to his neighbors, and worse still, to prevent them from concentrating their thoughts on Father Claver's instruction, he would throw his cloak over him as a screen. Again, he would often use his cloak as a cushion for the infirm. On such occasions the cloak was often withdrawn so infected and filthy as to require most drastic cleansing. Father Claver, however, was so engrossed in his work, that he would have resumed his cloak immediately had not his interpreters forcibly prevented him.

This cloak was to serve many purposes during his ministry: as a veil to disguise repulsive wounds, as a shield for leprous Negroes, as a pall for those who had died, as a pillow for the sick. The cloak was soon to acquire a legendary fame. Its very touch cured the sick and revived the dying. Men fought to come into contact with it, to tear fragments from it as relics. Indeed, before long its edge was ragged with torn shreds.

Claver's work was not confined to Cartagena. Cartagena was a slave mart, and very few slaves whom Father Claver baptized in Cartagena remained there. Now, Father Claver was determined not to lose his converts, and it was therefore his practice to conduct a series of country missions after Easter. He went from village to village, crossing mountain ranges, traversing swamps and bogs, making his way through forests.

On arriving in a village he would plant a cross in the market place, and there he would await the sunset and the return from the fields of the slaves whom he had first met. It might have been some weeks, it might have been some years before in Cartagena. The ecstatic welcome which marked these scenes of reunion were a royal recompense for the hardships of the missionary journey.

Father Claver never lost his ascendancy over the men whom he had baptized. On one occasion a mere message from him was sufficient to arrest the flight of a panic-stricken Negro population retreating in disorder from a volcano in eruption. Father Claver's messenger stopped the rout, and Father Claver's bodily presence next day transformed a terror-infected mob into a calm and orderly procession which followed him without fear round the very edge of the still active crater, on the crest of which Father Claver planted a triumphant cross.

Though Father Claver's activities were not confined to the Negroes, the "slave of the slaves" regarded himself as, above all, consecrated to their service. Proud Spaniards who sought him out had to be content with such time as he could spare from the ministrations of the Negroes. This attitude did not meet with universal approval. Spanish ladies complained that the smell of the Negroes who had attended Father Claver's daybreak Mass clung tenaciously to the church, and rendered its interior insupportable to sensitive nostrils for the remainder of the day.

How could they possibly be expected to confess to Father Claver in a confessional used by Negroes and impregnated with their presence? "I quite agree," replied Father Claver, with the disarming simplicity of the saint. "I am not the proper confessor for fine ladies. You should go to some other confessor. My confessional was never meant for ladies of quality. It is too narrow for their gowns. It is only suited to poor Negresses."

But were his Spanish ladies satisfied with this reply? Not a bit. It was Father Claver to whom they wished to confess, and if the worst had come to the worst, they were prepared to use the same confessional as the Negresses. "Very well, then," replied Father Claver, meekly, "but I am afraid you must wait until all my Negresses have been absolved."

—Excerpts from A Saint in the Slave Trade by Arnold Lunn