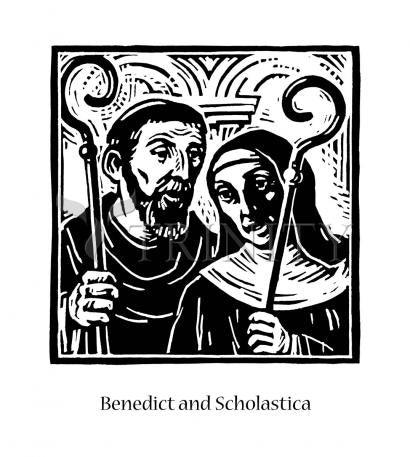

Collection: Sts. Benedict and Scholastica

-

Sale

Wood Plaque Premium

Regular price From $99.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$111.06 USDSale price From $99.95 USDSale -

Sale

Wood Plaque

Regular price From $34.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$38.83 USDSale price From $34.95 USDSale -

Sale

Wall Frame Espresso

Regular price From $109.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$122.17 USDSale price From $109.95 USDSale -

Sale

Wall Frame Gold

Regular price From $109.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$122.17 USDSale price From $109.95 USDSale -

Sale

Wall Frame Black

Regular price From $109.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$122.17 USDSale price From $109.95 USDSale -

Sale

Canvas Print

Regular price From $84.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$94.39 USDSale price From $84.95 USDSale -

Sale

Metal Print

Regular price From $94.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$105.50 USDSale price From $94.95 USDSale -

Sale

Acrylic Print

Regular price From $94.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$105.50 USDSale price From $94.95 USDSale -

Sale

Giclée Print

Regular price From $19.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$22.17 USDSale price From $19.95 USDSale -

Custom Text Note Card

Regular price From $300.00 USDRegular priceUnit price per$333.33 USDSale price From $300.00 USDSale

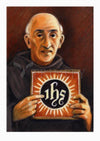

ARTIST: Julie Lonneman

ARTWORK NARRATIVE:

Once a year, Benedict and Scholastica would meet together. During this annual visit, Benedict and Scholastica would talk about God for hours. On one particular visit, after they dined together, Benedict was preparing to leave, but Scholastica begged him to stay so that they might continue their conversation. However, Benedict’s rule did not allow him to spend a night away from the monastery. Scholastica prayed that God might allow Benedict to stay for the evening. Suddenly, there was a huge rainstorm, so large that Benedict did have to remain in the shelter with his sister. Only three days later, Scholastica died. While Benedict had at first been annoyed by his sister’s prayer, through it he eventually came to see that the greatest work that he could do was not to keep his rule, but to love each person he met by giving each person his full attention.

—ND Vision, University of Notre Dame

Italy, 480-547 and 480-543.

Their feast days are July 11 and February 10.

- Art Collection:

-

Saints & Angels

- Patronage:

-

Witchcraft,

-

Temptations,

-

Storms,

-

Schoolchildren,

-

Religious Orders,

-

Rain,

-

Nuns,

-

Monks,

-

Kidney Disease,

-

Italy,

-

Fever,

-

Farmers,

-

Europe,

-

Dying,

-

Coppersmiths,

-

Convulsions,

-

Civil Engineers,

-

Cavers,

-

Agricultural Workers,

-

Poisoning

- Lonneman collection:

-

Models of Faith

On the occasion of the dedication of the rebuilt monastery of Monte Cassino in 1964, Pope Paul VI proclaimed St. Benedict the principal, heavenly patron of the whole of Europe. The title piously exaggerates the place of Benedict but in many respects it is true. St. Benedict did not establish the monastery of Monte Cassino in order to preserve the learning of the ages, but in fact the monasteries that later followed his Rule were places where learning and manuscripts were preserved. For some six centuries or more the Christian culture of medieval Europe was nearly identical with the monastic centers of piety and learning.

Saint Benedict was not the founder of Christian monasticism, since he lived two and a half to three centuries after its beginnings in Egypt, Palestine, and Asia Minor. He became a monk as a young man and thereafter learned the tradition by associating with monks and reading the monastic literature. He was caught up in the monastic movement but ended by channeling the stream into new and fruitful ways. This is evident in the Rule which he wrote for monasteries and which was and is still used in many monasteries and convents around the world.

Tradition teaches that St. Benedict lived from 480 to 547, though we cannot be sure that these dates are historically accurate. His biographer, St. Gregory the Great, pope from 590 to 604, does not record the dates of his birth and death, though he refers to a Rule written by Benedict. Scholars debate the dating of the Rule though they seem to agree that it was written in the second third of the sixth century.

Saint Gregory wrote about St. Benedict in his Second Book of Dialogues, but his account of the life and miracles of Benedict cannot be regarded as a biography in the modern sense of the term. Gregory's purpose in writing Benedict's life was to edify and to inspire, not to seek out the particulars of his daily life. Gregory sought to show that saints of God, particularly St. Benedict, were still operative in the Christian Church in spite of all the political and religious chaos present in the realm. At the same time it would be inaccurate to claim that Gregory presented no facts about Benedict's life and works.

According to Gregory's Dialogues Benedict was born in Nursia, a village high in the mountains northeast of Rome. His parents sent him to Rome for classical studies but he found the life of the eternal city too degenerate for his tastes. Consequently he fled to a place southeast of Rome called Subiaco where he lived as a hermit for three years tended by the monk Romanus.

The hermit, Benedict, was then discovered by a group of monks who prevailed upon him to become their spiritual leader. His regime soon became too much for the lukewarm monks so they plotted to poison him. Gregory recounts the tale of Benedict's rescue; when he blessed the pitcher of poisoned wine, it broke into many pieces. Thereafter he left the undisciplined monks.

Benedict left the wayward monks and established twelve monasteries with twelve monks each in the area south of Rome. Later, perhaps in 529, he moved to Monte Cassino, about eighty miles southeast of Rome; there he destroyed the pagan temple dedicated to Apollo and built his premier monastery. It was there too that he wrote the Rule for the monastery of Monte Cassino though he envisioned that it could be used elsewhere.

The thirty-eight short chapters of the Second Book of Dialogues contain accounts of Benedict's life and miracles. Some chapters recount his ability to read other persons' minds; other chapters tell of his miraculous works, e.g., making water flow from rocks, sending a disciple to walk on the water, making oil continue to flow from a flask. The miracle stories echo the events of certain prophets of Israel as well as happenings in the life of Jesus. The message is clear: Benedict's holiness mirrors the saints and prophets of old and God has not abandoned his people; he continues to bless them with holy persons.

Benedict is viewed as a monastic leader, not a scholar. Still he probably read Latin rather well, an ability that gave him access to the works of Cassian and other monastic writings, both rules and sayings. The Rule is the sole known example of Benedict's writing, but it manifests his genius to crystallize the best of the monastic tradition and to pass it on to the European West.

Gregory presents Benedict as the model of a saint who flees temptation to pursue a life of attention to God. Through a balanced pattern of living and praying Benedict reached the point where he glimpsed the glory of God. Gregory recounts a vision that Benedict received toward the end of his life: In the dead of night he suddenly beheld a flood of light shining down from above more brilliant than the sun, and with it every trace of darkness cleared away. According to his own description, the whole world was gathered up before his eyes "in what appeared to be a single ray of light." St. Benedict, the monk par excellence, led a monastic life that reached the vision of God.

Born: c.480, Narsia, Umbria, Italy

Died: March 21, 547 of a fever while in prayer at Monte Cassino, Italy; buried beneath the high altar there in the same tomb as Saint Scholastica.

Name Meaning: Blessed

—Excerpts from The Modern Catholic Encyclopedia (A Michael Glazier Book), Liturgical Press (1995) 78-79.

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE: Of a Miracle Wrought by his Sister, Scholastica.

GREGORY: Who is there, Peter, in this world, that is in greater favor with God than St. Paul? Three times he petitioned our Lord to be delivered from the thorn of the flesh, and yet he did not obtain his petition. Speaking of that, I must tell you how there was one thing which the venerable father Benedict would have liked to do, but he could not.

His sister, named Scholastica, was dedicated from her infancy to our Lord. Once a year she came to visit her brother. The man of God went to her not far from the gate of his monastery, at a place that belonged to the Abbey. It was there he would entertain her. Once upon a time she came to visit according to her custom, and her venerable brother with his monks went there to meet her.

They spent the whole day in the praises of God and spiritual talk, and when it was almost night, they dined together. As they were yet sitting at the table, talking of devout matters, it began to get dark. The holy Nun, his sister, entreated him to stay there all night that they might spend it in discoursing of the joys of heaven. By no persuasion, however, would he agree to that, saying that he might not by any means stay all night outside of his Abbey.

At that time, the sky was so clear that no cloud was to be seen. The Nun, hearing this denial of her brother, joined her hands together, laid them on the table, bowed her head on her hands, and prayed to almighty God.

Lifting her head from the table, there fell suddenly such a tempest of lightning and thundering, and such abundance of rain, that neither venerable Benedict, nor his monks that were with him, could put their heads out of doors. The holy Nun, having rested her head on her hands, poured forth such a flood of tears on the table, that she transformed the clear air to a watery sky.

After the end of her devotions, that storm of rain followed; her prayer and the rain so met together, that as she lifted up her head from the table, the thunder began. So it was that in one and the very same instant that she lifted up her head, she brought down the rain.

The man of God, seeing that he could not, in the midst of such thunder and lightning and great abundance of rain return to his Abbey, began to be heavy and to complain to his sister, saying: "God forgive you, what have you done?" She answered him, "I desired you to stay, and you would not hear me; I have desired it of our good Lord, and he has granted my petition. Therefore if you can now depart, in God's name return to your monastery, and leave me here alone."

Departure Delayed:

But the good father, not being able to leave, tarried there against his will where before he would not have stayed willingly. By that means, they watched all night and with spiritual and heavenly talk mutually comforted one another.

Therefore, by this we see, as I said before, that he would have had one thing, but he could not effect it. For if we know the venerable man's mind, there is no question but that he would have had the same fair weather to have continued as it was when he left his monastery. He found, however, that a miracle prevented his desire. A miracle that, by the power of almighty God, a woman's prayers had wrought.

Is it not a thing to be marveled at, that a woman, who for a long time had not seen her brother, might do more in that instance than he could? She realized, according to the saying of St. John, "God is charity." Therefore, as is right, she who loved more, did more.

PETER: I confess that I am wonderfully pleased with that which you tell me.

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR: How Benedict Saw the Soul of his Sister Ascend into Heavenly Glory.

GREGORY: The next day the venerable woman returned to her nunnery, and the man of God to his abbey. Three days later, standing in his cell, and lifting up his eyes to heaven, he beheld the soul of his sister (which was departed from her body) ascend into heaven in the likeness of a dove.

Rejoicing much to see her great glory, with hymns and praise he gave thanks to almighty God, and imparted the news of her death to his monks. He sent them presently to bring her corpse to his Abbey, to have it buried in that grave which he had provided for himself. By this means it fell out that, as their souls were always one in God while they lived, so their bodies continued together after their death.

Born: 480

Died: 543 of natural causes

Name Meaning: She who has leisure to devote to study

—Excerpts from Gregory the Great (c. 540-604), Dialogues, Book II (Life and Miracles of St. Benedict). Courtesy of the Saint Pachomius Library

Additional Items Our Customers Like

-

St. Benedict of Nursia (by Museum Religious Art Classics)

-

St. Benedict of Nursia (by Joan Cole)

-

St. Benedict of Nursia (by Brenda Nippert)

-

St. Benedict of Nursia - Angel Pointing to Monastery of Mont Cassino (by Museum Religious Art Classics)

-

St. Benhilde Romançon (by Julie Lonneman)

-

St. Bernardine of Siena (by Julie Lonneman)