Collection: Simone Weil

-

Sale

Wood Plaque Premium

Regular price From $99.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$111.06 USDSale price From $99.95 USDSale -

Sale

Wood Plaque

Regular price From $34.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$38.83 USDSale price From $34.95 USDSale -

Sale

Wall Frame Espresso

Regular price From $109.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$122.17 USDSale price From $109.95 USDSale -

Sale

Wall Frame Gold

Regular price From $109.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$122.17 USDSale price From $109.95 USDSale -

Sale

Wall Frame Black

Regular price From $109.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$122.17 USDSale price From $109.95 USDSale -

Sale

Canvas Print

Regular price From $84.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$94.39 USDSale price From $84.95 USDSale -

Sale

Metal Print

Regular price From $94.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$105.50 USDSale price From $94.95 USDSale -

Sale

Acrylic Print

Regular price From $94.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$105.50 USDSale price From $94.95 USDSale -

Sale

Giclée Print

Regular price From $19.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$22.17 USDSale price From $19.95 USDSale -

Custom Text Note Card

Regular price From $300.00 USDRegular priceUnit price per$333.33 USDSale price From $300.00 USDSale

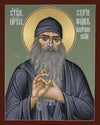

ARTIST: Br. Robert Lentz, OFM

ARTWORK NARRATIVE:

Simone Weil grew up in an affluent, middle class, agnostic family in France. In spite of her comfortable surroundings and the poor health she suffered from infancy, she identified with suffering humanity her entire life and tried to stand in solidarity with the poor. When she was only six years old she refused to eat sugar because French soldiers fighting on the front had none. When she was 10 she declared herself a Bolshevik. She died in England of tuberculosis and malnutrition during World War II, refusing to eat more than what French people received as rations.

The Gregorian Chant in the background of this icon comes from the Lamentations of Jeremiah, once sung during Matins on Thursday of Holy Week. Unlike most left-leaning activists of her time, Simone was a Christian mystic whose prolific writings explore affliction, beauty, and love. She saw the greatest possible expression of love in the divine love that spanned the infinite separation between the crucified, incarnate Christ and God the Father:

“This tearing apart, over which supreme love places the bond of supreme union, echoes perpetually across the universe in the depth of silence, like two notes, separate yet blending into one, like a pure and heartrending harmony. This is the Word of God. The whole creation is nothing but its vibration. When human music in its greatest purity pierces our soul, this is what we hear through it. When we have learned to hear the silence, this is what we grasp, even more distinctly, through it.”

“Those who persevere in love hear this note from the very lowest depths into which affliction has thrust them. From that moment they can no longer have any doubt.”(The Love of God)

Throughout her life she refused Catholic baptism because she feared it would separate her from countless holy people in other religious traditions. Finally, on her deathbed, she accepted baptism from a lay person, but she never received the Eucharist she had so often contemplated in Catholic churches.

- Lentz collection:

-

Ecumenical Icons

French philosopher, activist, and religious searcher, whose death in 1943 was hastened by starvation. Weil published during her lifetime only a few poems and articles. With her posthumous works - 16 volumes, edited by André A. Devaux and Florence de Lussy - Weil has earned a reputation as one of the most original thinkers of her era. T.S. Eliot described her as "a woman of genius, of a kind of genius akin to that of the saints."

Simone Weil was born in Paris in her parent's apartment on the Rue de Strasbourg. Later the family moved to a larger flat on the Boulevard Saint-Michel. Simone was raised in an agnostic Jewish family. Her father, Bernard Weil, was an Alsace physician and her mother (née Salomea Reinherz), was Austro-Galician. Salomea - or Selma - came from a wealthy family of Jewish businessmen. She had wanted to become a doctor but her father forbad it. For her own amazing children she wanted the best education available. Weil's brother André solved mathematical problems beyond the doctoral level at the age of twelve; he became a distinguished mathematician. Selma Weil's solicitude had also an excessive side - she had a phobic dread of microbes and imposed on her children compulsive hand washing. Mme. Weil ruled, that outside the immediate family, nobody else was allowed to kiss the children. Throughout her life, Simone avoided most forms of physical contact. She also had problems with food. At the age of six she refused to eat sugar, because it was not rationed to French soldiers in the war. In the late 1930s, possibly due to her malnutrition, she had mystical experiences.

In her early teens, Weil mastered Greek and several modern languages. With André, she sometimes communicated in ancient Greek. When after the Russian Revolution she was accused of being a Communist by a classmate, she answered: "Not at all; I am a Bolshevik." Weil studied at the Lycée Fénelon (1920-24) and Lycée Victor Duruy, Paris (1924-25), graduating with baccalauréat. She then continued her studies at the Lycée Henri IV (1925-28), where she was taught by the noted French philosopher Alain, pseudonym of Emile Auguste Chartier (1868-1951). He trained his students to think critically by assigning them topoi, take-home essay examinations. In 1928, Weil finished first in the entrance examination for the École Normale Supérieure; Simone de Beauvoir finished second. During the following years Weil attracted much attention with her uncompromising attitudes. Around the Left Bank of Paris, the myopic and awkward Weil was called the "Red Virgin."

In 1931 Weil received her agrégation in philosophy. Though physically weak, she alternated stints of teaching philosophy with manual labor in factories and fields, in order to understand the real needs of the workers. She insisted that writing should be based on experience. "The intelligent man who is proud of his intelligence is like the condemned man who is proud of his cell," she once said. Between the years 1931 and 1938, she was employed by various schools in Le Puy, Auxerre, Roanne, Bourges, and Saint-Quentin. "Whenever, in life, one is actively involved in something, or one suffers violently, one cannot think about oneself," Weil taught at the lycée for girls at Roanne.

Weil did not associate with her teacher colleagues but preferred the company of workers and sat with them in cafés. Her salary she shared with the unemployed. After participating in a protest march, she was forced to resign from Le Puy-en-Velay high school. In 1934-35 she was a "hopelessly inept" factory worker for Renault, Alsthom, and Carnaud. This hard period nearly crushed her emotionally and physically - she had abnormally small, feeble hands - as she confessed in her diary. In spite of her pacifist beliefs, she served in 1936 briefly as a volunteer with the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War. The novelist Georges Bataille described her as "a Don Quixot". "'I knew her very well,' Trotsky wrote in a letter of July 30, 1936, to his comrade Victor Serge. 'I have had long discussions with her. For a period of time she was more or less in sympathy with our cause, but then she lost faith in the proletariat and in Marxism. It's possible that she will turn toward the left again. But is it worth the trouble to talk about this any longer?'" (from The Left Hand of God by Adolf Holl, 1997). Armed with a rifle but nearsighted, she was a danger to everyone around her, including herself. A clumsy accident — she stuck her foot in a pot of boiling cooking oil and suffered a severe burn — forced her to leave the front, and she went to Portugal to recuperate. To the moral problem with which she had wrestled secretly, would she try to kill the enemy, and in the process, risk killing an innocent victim, she never found an answer.

After witnessing the horrors of war in Spain, Weil revealed in her journals her deepening disillusionment with ideologies. She saw that Communism led to the formation of a State dictatorship. "From human beings, no help can be expected," she wrote already in 1934. Sex was something she was afraid of. Her pacifist stance she later considered a mistake, saying: "If Mr. Gandhi can protect his sister from rape through non-violent means, then I will be a pacifist." For a time she felt attraction to Anarchism and Syndicalism and she worked for the anarchist trade union movement La Révolution Prolétarianne. In the mid-1930s Weil became increasingly drawn to Christianity. However, she refused baptism into the Catholic Church.

Upon returning to France, she obtained a teaching post at Saint-Quentin. Headaches continued to plague her. In 1938 she converted from Judaism to Christianity. Weil studied Greek poetry and Gregorian music, and in 1937 at the chapel of St. Francis of Assisi, in Assisi, Italy, she had one of her mystical experiences. Occasionally she dressed in the clothes of a poor monk or a soldier. In 1940 the Vichy anti-Jewish laws required her dismissal from teaching.

During the first years of World War II Weil lived with her parents in Paris, Vichy, and Marseilles. She continued to write and worked at Gustave Thibon's vineyards in Saint-Marcel d'Ardéche. Before leaving France, she gave to Thibon her notebooks and other papers, which formed the core of her posthumous works. In Marseilles she met Father Joseph-Marie Perrin, with whom she had long discussions, but refused finally his offer to baptize her into the Catholic faith. She fled from Nazi occupation to the United States and then to England in 1942, where she worked for the Ministry of the Interior in De Gaulle's Free French movement in 1943. Weil died at the age of 34 of tuberculosis and self-neglect in Ashford on August 24, 1943. She refused food and medical treatment out of sympathy for the plight of the people of Occupied France. This act hastened her death, although it is debated whether her death was a result of actual suicide or mental illness. Weil also believed that one must "decreate" oneself to return to God.

Weil's early essays were published in Alain's Libre Propos. From 1940 she contributed to Les Cahiers du Sud. Weil's writings from her first period (1931-36) explore contemporary problems. The later writings (1938-43) reflect her religious searching. In Gravity and Grace (1947) she stated that "attachment is the great fabricator of illusions; reality can be attained only by someone who is detached." God, in creating the universe, effaced himself from it and surrendered it to its own law of gravity, or necessity. "Necessity is everywhere, and the good nowhere," she wrote. 'La pesanteur' or gravity meant in Weil's text undeveloped, primitive forces in human beings. Another force, in conflict with it, is God's grace. "Two forces prevail in the universe: light and gravity." Weil's political philosophy is best expressed in the The Need for Roots (1953). The great problem of society is 'déracinement', its 'uprootedness'; its cure is a social order grounded in a 'spiritual core' of physical labor. One can find from work beauty, poetry and spiritual inspiration. She wrote the book in 1943 at the request of the Free French organization as a guide to the reconstruction of post-war France. In Oppression and Liberty (1955) she is concerned with the nature and possibility of individual freedom in various political and social systems, finally opting for liberalism rather than socialism.

—Excerpts from“Simone Weil (1909 — 1943)" by Petri Liukkonen

Additional Items Our Customers Like

-

Elijah (by Louis Glanzman)

-

Entombment (by Museum Religious Art Classics)

-

Eucharist (by Julie Lonneman)

-

Eve, The Mother of All (by Br. Robert Lentz, OFM)

-

Exalt Not in the Cross (by Dan Paulos)

-

Exhumation of St. Hubert (by Museum Religious Art Classics)

-

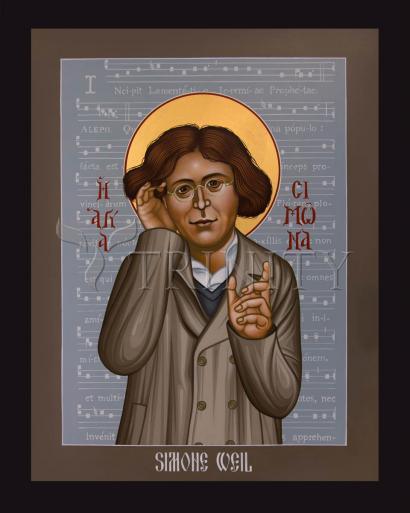

Seraphim Rose of Platina (by Br. Robert Lentz, OFM)

-

Pedro Arrupe, SJ (by Br. Robert Lentz, OFM)

-

Syro-Phoenician Woman (by Br. Robert Lentz, OFM)

-

Sweetest Gift, A Mother's Smile (by Dan Paulos)

-

Sun of Justice (by Julie Lonneman)

-

Sts. Mary, Ann, Kateri - Holy Women Pray for Us (by Br. Mickey McGrath, OSFS)